Trans-Uganda

Words: Evan Christenson

Photos: Evan Christenson

The Trans-Uganda is a challenge with peaks, valleys and deserts unlike any you have ever faced. The route you can extend to begins with a several hour, 15-20% mud slog up Mt Elgon- a dormant volcano on the Eastern border with Kenya where children will push your bike for hours and laugh, smile and shout when paid $0.20 for their work. Then you slide down the mud to isolated camping underneath waterfalls where city lights fade and small huts hand out cold, cheap beer and hearty, guttural laughter. It then involves long, 200km days of remote dirt roads to the Northern border with South Sudan. Along these roads are nomads driving hundreds of bulls you have to navigate. There’s limited food and water along the several hour climbs to reach the high desert, and it’s here tsetse flies swarm your body and chew to its center. The searing heat makes you reach for empty bottles again and again and the mind turns to mush in the dragging, thankless quiet so polarizing from the city a week prior. The clay roads will eventually turn to wet cement in the rain and you’re forced to push the additional 10kg of mud, sliding and cursing all the while. The unpredictability of the weather on the shoulders of the dry and wet seasons means this slog of mud comes and goes for endless kilometers and endless days.

The route then brings you west, where you climb steep, loose backroad climbs for hours to approach the foot of the Rwenzori mountains. You then begin the climb into the mountains on the border with Congo where the rain turns to snow and the peaks reach to replace the sky and dance with the clouds. You then take the route south to hack through the jungle in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park and descend to the Southern border where large volcanoes border Rwanda. You then ride back east towards the capital, Kampala, where you left your backpack and bike box. You take a ferry to the island Kalangala in Lake Victoria where the next ferry brings a very much overcrowded and bustling group back to the start of the route where you can’t resist the urge and break down crying on the side of the road.

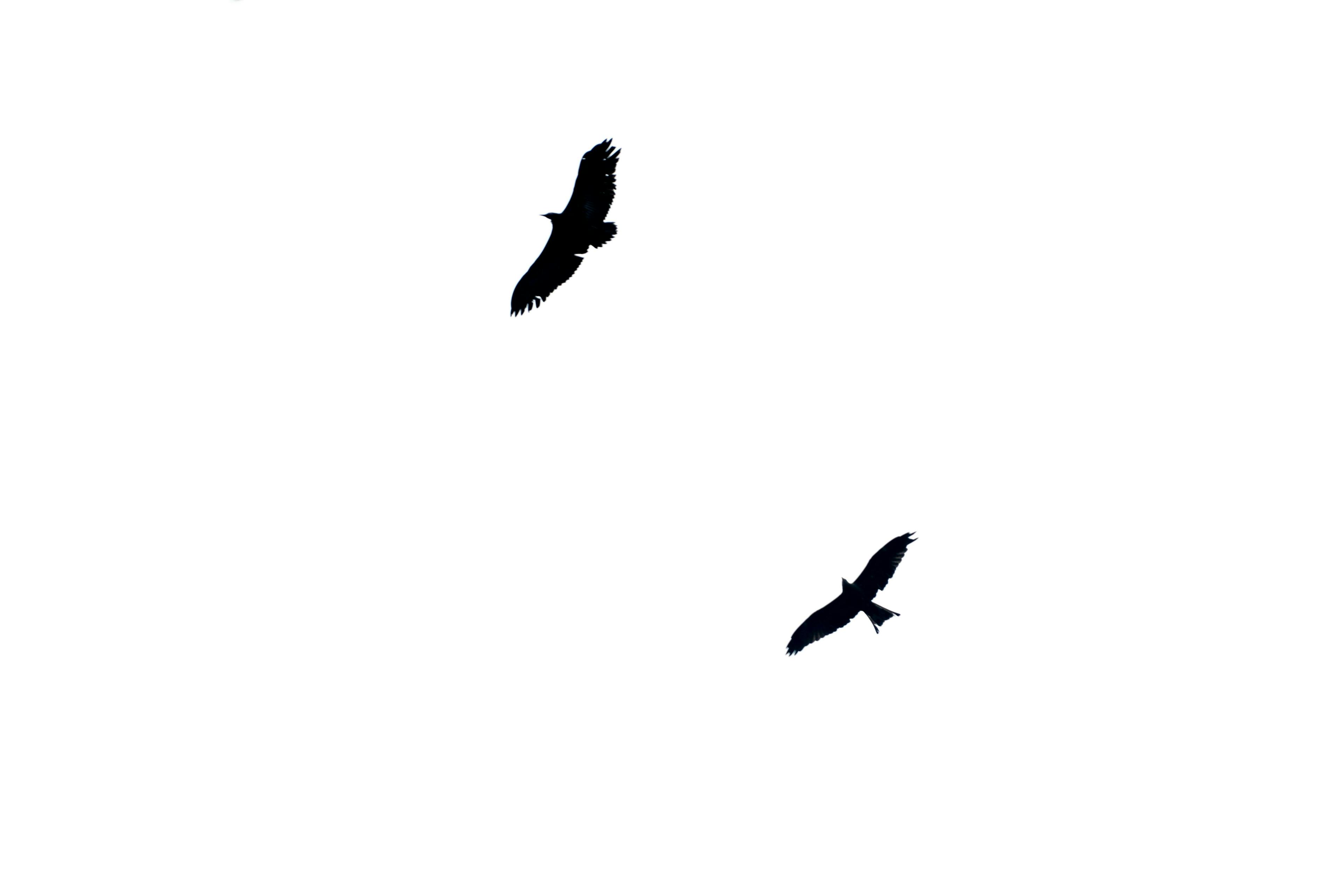

Why? Because all along the way you’ve ridden 2,300 miles in five weeks, almost all completely alone where intense, gripping poverty is the only world you have. Children run, scream and chase every minute of every day and the cars honk and motorcyclists grab at the all too foreign and novel Mizungu. You run from disease and find food poisoning through wrong turns and misdirections lost in rough translation. You wait out storms in huts, houses, markets and bridge underpasses and hide from terrifying thunder in roadside gutters. You sit in a truck bed to evade your first wild pack of baboons. You ride with locals, eat with locals and laugh with locals because they become shadows of curiosity illuminating and stepping forward while the pedals continue to fall. They become your haven, and some quickly become your family. Throughout the route you cross game parks where zebras run in packs through the plains 20 meters off your flank and giraffes stumble about the roads. You find monkeys jumping through the trees you camp under and elephants crossing roads and holding up traffic. You can’t stop reaching for the camera and gasping. It never gets old.

Along the route you cross the Nile again again again and again until it becomes an old friend that will linger in the places you ride slowly and roar with veracity when you descend white knuckled over its bridges. Throughout the route you’re asked unending questions on who you are and where you’re from and why you came alone to Uganda. These questions prod at the hard underlying questions of self and of identity and you must sit there and chew on them for the 10 hours you pedal the next day. Along the way you talk politics and learn of the turmoil and corruption that has defined this area of the world for decades. You begin to understand how the happiness promised in strip malls back home is redefined here as a naturally irrefutable escaping of soul and a prideful integration of community and family.

The route makes you question everything you have at home and everything you care about at home and how little those two very different things overlap. The route beats you. It kicks you, bucks you and eats you. It leaves you crying in the shower at night and hungover in the morning and when you finally finish it and look out of your airplane window at a city of dirt you’re filled with hatred. Flaming, effusive, hatred for this western plane for making this country of dirt smaller and smaller and bringing you further away from where you shattered all the rigidity of home and were left to reassemble it however you chose.

The Trans-Uganda is brutal. It reaches towards death and in this stretch gives you a bridge to life if you are willing to step out and try to cross it. And I hope you are. I really hope you are.

I stepped. No, I LEAPT and crossed the Trans-Uganda (++, 2 extensions) this past month. I slept and rode for 36 days and almost every morning I’d wake up in a new town and begin the process all over again. Find breakfast, (mostly fruits and bread, omelettes too) and put back on the same kit: Farside shorts light for the miles and still dirty from the mud baths of Mt Elgon. MK3 bibs supportive through yet another 10 hours today. Ashlu socks not washed for four days, and an El Dorado shirt I wore to the bar the night prior and will pour water all over as the midday sun begins its midday burn. Then pack the tent and the saddlepack and begin the day’s ride. It’s time to find enlightenment. And I think today it’s lying to the west.

Follow Evans Instagram for more inspiring adventures and photos and learn more about the Trans-Uganda route at Bikepacking,com